Cyclone Engineers have developed a new smart and responsive material that stiffens up like a worked-out muscle.

Stress a muscle and it gets stronger. Mechanically stress the rubbery material – say with a twist or a bend – and the material automatically stiffens by up to 300 percent, the engineers said. In lab tests, mechanical stresses transformed a flexible strip of the material into a hard composite that can support 50 times its own weight. This new composite material doesn’t need outside energy sources, such as heat, light or electricity to change its properties. And it could be used in a variety of ways, including applications in medicine and industry.

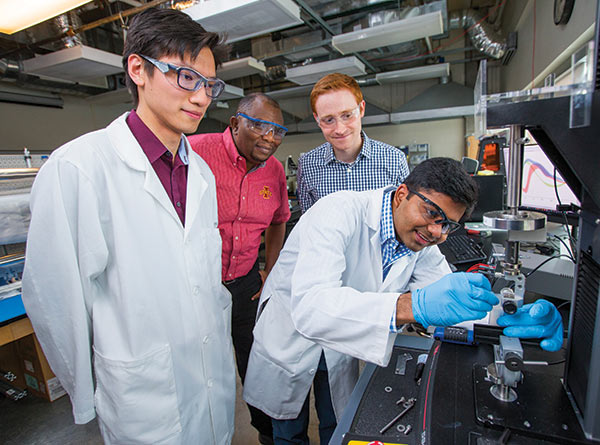

Lead researchers are Martin Thuo and Michael Bartlett, both assistant professors of materials science and engineering, who combined Thuo’s expertise in micro-sized, liquid-metal particles with Bartlett’s expertise in soft materials such as rubbers, plastics and gels. The researchers found a simple, low-cost way to produce particles of undercooled metal – that’s metal that remains liquid even below its melting temperature. The tiny particles (they’re just 1 to 20 millionths of a meter across) are created by exposing droplets of melted metal to oxygen, creating an oxidation layer that coats the droplets and stops the liquid metal from turning solid. They also found ways to mix the liquid-metal particles with a rubbery elastomer material without breaking the particles.

When this hybrid material is subject to mechanical stresses – pushing, twisting, bending, squeezing – the liquid-metal particles break open. The liquid-metal flows out of the oxide shell, fuses together and solidifies.

“You can squeeze these particles just like a balloon,” Thuo said. “When they pop, that’s what makes the metal flow and solidify.”

The result, Bartlett said, is a “metal mesh that forms inside the material.”

Thuo and Bartlett said the popping point can be tuned to make the liquid metal flow after varying amounts of mechanical stress. Tuning could involve changing the metal used, changing the particle sizes or changing the soft material. In this case, the liquid-metal particles contain Field’s metal, an alloy of bismuth, indium and tin. But Thuo said other metals will work, too.

“The idea is that no matter what metal you can get to undercool, you’ll get the same behavior,” he said.

The engineers say the new material could be used in medicine to support delicate tissues or in industry to protect valuable sensors. There could also be uses in soft and bioinspired robotics or reconfigurable and wearable electronics.

“A device with this material can flex up to a certain amount of load,” Bartlett said. “But if you continue stressing it, the elastomer will stiffen and stop or slow down these forces.”